A few years ago I was awarded a residency in the factories of Germany. Just imagine, every girl’s dream: a six week all-expense paid trip to Nuremberg, free access to heavy machinery, and the opportunity to observe, experience, and smell the factories of one of Germany’s leading industrial cities! For me, it was a thrill. I was fascinated by machine sounds and factory environments, but I never had the chance to witness them first hand. This program, designed to “combine art and industry,” helped me realize my dream and get my hands and my ears dirty in an industrial environment.

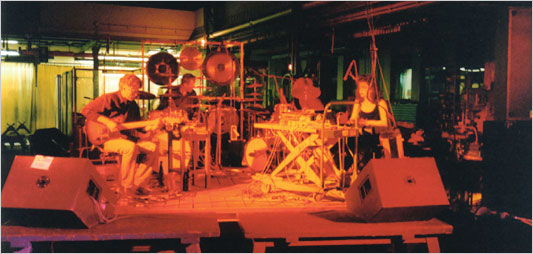

It was there that I developed my concert-length piece “EWA7,” which became a turning point for me, an amazing chance to mold, alter, and structure noise to create music. Since the premiere in Nuremberg in 1999, it has been performed at a destroyed factory in Warsaw, at the Anchorage below the Brooklyn Bridge, and at clubs and concert halls all over the world. Most recently I performed a trio version with myself, Roger Kleier on guitar, and Ches Smith on percussion, that was performed at Merkin Hall on May 3. I also recorded the piece on my CD, “Flying Sparks and Heavy Machinery.”

When I arrived in Nuremberg, I began a long string of factory visits, microphone and recorder in hand, hosted by Jens Cording and the Siemens Foundation. I loved walking through a factory and hearing sounds develop in all frequencies, from the high–pitched buzz of the lights to sub-audio rumbles. The sonic environment of each factory was constantly changing as individual machines turned on and off, workers chatted, radios played, and the natural polyrhythms of the combined machines cycled and shifted. The musical cliche of relentlessly repeating machine sounds simply didn’t exist. Some factories were so huge that the workers used bicycles to deliver parts from one end of the hall to the other, and the massive spaces created huge variations in sound.

An important part of the residency was the opportunity to listen: what I initially heard as a mass of cacophonous factory noise gradually revealed itself to be a beautifully complex amalgam of layered textures and timbres. The sound of a buzzsaw’s rising harmonic grind would emerge out of the quiet ambient hum of fluorescent lights, only to be obliterated by random arrhythmic crashes and bangs from a huge metal press. Machine rhythms went in and out of phase, and dynamics varied wildly in an environment of constantly shifting activity and noise.

The best sounds always came from the stinkiest factories. The crashes and bangs of heavy industry were much more dramatic than the beeps and blips of the antiseptic “clean rooms.” Metal presses created rhythms that had fascinating variations in each repeat, and the sounds of welding areas were rich with harmonics and the faint whiff of toxic fumes.

After completing my initial research, I decided to write a site-specific piece that would be performed in the EWA7 factory, composed for sampled factory sounds, electric guitar, drums, and percussion played on machines and found factory metal. I enlisted two local percussionists, Hans-Gunter Brodmann, and Matthias Rosenbauer, along with Roger Kleier, who had traveled from New York to Nuremberg with me.

In order to find interesting site-specific materials, I brought the percussionists to EWA7. Armed with drum sticks, mallets, and hammers, we combed the space in search of anything to beat, scratch, rattle, or shake, ranging from small bits of pipe to enormous metal acid baths. The drummers crashed and banged their way through the factory, with a junk percussionist’s sixth sense of what sounded best, and sniffed out a treasure trove of discarded metal in a shack behind the factory. Most importantly, we discovered that the factory’s soda machine was stocked with bottles of beer.

The piece was composed with regard to space as well as sound. The percussionists were totally mobile, bringing their sticks and mallets to any location to beat on an assortment of beautiful, resonant pieces of metal and machinery. I was stuck on stage, tethered to my keyboard, so I arranged to have the workers bring a machine to me: a giant safety buzzer. I loved my new industrial weapon. It was attached by thick cables to an enormous overhead crane, and delivered to me by Hans and Harald, two workers from the factory dressed in bright blue overalls. I used the buzzer it to blast the percussionists when their solos got too long. Who needs a baton? Every conductor should have one of these!

In advance of the concert, Siemens arranged a press conference. I felt like a sheep in wolf’s clothing: the new music composer disguised as C.E.O. One journalist asked me what Americans knew about Nuremberg; I told him that we had all heard about the Nuremberg trials and Nazi rallies. Somehow it got lost in translation; he reported that Americans were all familiar with Nuremberg’s famous race car rallies!

I titled the piece “EWA7.” The performance would be one continuous hour of individually structured pieces, overlapping sounds, and improvised sections. The intended effect was that of walking through a large factory and experiencing the gradual shifts in timbre, rhythm, and ambient sounds that occur as the industrial environment changes. Driving machine samples, layers of ambient noise, crashing metal and electronic blips and bleeps would all meld and collide, evoking the clamor and din of a journey through a grimy working factory.

Since this wasn’t a regular concert venue, we had no idea who would show up. The audience wound up being a wild mix of industrialists, workers, Siemens executives, artists, journalists, cultural officers, arts supporters, and the local anarchist contingent. I definitely was not preaching to the converted. Three consecutive speeches were being delivered in the foyer of the factory while I was interviewed by the local TV station. The TV interview came through without a hitch until I realized that I had been swinging around big glass of whiskey for the entire taping. I guess there’s a little Dean Martin in all of us.

While the crowd was listening to speeches in the foyer, I snuck the band onstage to start “Rotation,” a piece based on the simple sounds of an engine starting. The piece faded in slowly, and as a quiet hum swelled in volume, it began the transformation from machine sounds to music.

The audience wandered in, unaware that the concert was starting, until their perception slowly shifted to hear the rising hum as music. Textures thickened as sustained guitar and bowed percussion blended with the soft whir of engine sounds.

The performance was a series of interlocking pieces for the full ensemble, interspersed with solos and duos. While I held the fort during a keyboard solo, the drummers snuck off stage, only to reappear on a balcony, furiously beating on ten–foot long mounted steel cylinders. Roger Kleier used small motors to excite the pickups of his electric guitar, bringing the buzzing, harmonically rich sounds of the factory directly to his instrument. Hans and Harald, our two volunteer workers from the factory, used an enormous overhead crane to transport a huge rusted metal acid–bath pool from behind the audience across the length of the factory. As the crane was lowered to its final destination in front of the stage, the two percussionists attacked the huge suspended metal object, in a duet of bowed, beaten, and scraped sounds.

For our final piece, “Combustion Chamber,” the percussionists wheeled out two industrial carts laden with rusty brake drums and pipes, which not only looked good, but sounded like Thor himself, if Thor had been a junk percussionist. “Combustion Chamber” is the loudest part of “EWA7,” with distorted guitar, machine and analog synthesizer samples, all propelled by metal percussion. At the end, the sampler and guitar dropped out, the machines stopped, and all that was left was a percussion battle of man and metal.

That battle went on and on, much longer than it ever had in rehearsal, until I reached for my newfound instrument, my beloved, deafening safety buzzer. And so, with one loud buzz, our work day was over, and man was stopped by machine.

“EWA7”was one hour long with no gaps, so there was no way to gauge what the reaction of the very mixed audience would be until the performance was over. I held my breath for a moment, then got the most heartfelt applause that I’ve ever experienced. Workers told me afterwards that they had never even thought about the sounds in their workplace, but that this experience would change how they listened to them forever. It was incredibly gratifying to learn that the piece meant something to them, and that I wasn’t the only one who experienced an epiphany of sound amid the grime and girly calendars of EWA7.

AFTER THE FACTORY

My time in Nuremberg had an indelible effect on my music. Soon after I returned home, I composed “Flying Sparks and Heavy Machinery,” a fully notated piece for string quartet and percussion quartet inspired by the ambience, energy, and sheer power of industrial sound. “The Harmony of the Body Machine,” for cello and tape, uses sweeping bandsaws, crashing metal presses, and percussive pile drivers, coupled with Joan Jeanrenaud’s incredible cello technique. “Lost Signals and Drifting Satellites” sneaks in a few factory sounds as well, blended with shortwave bleeps and buzzes, and George Kentros on violin.

Most of all, the experience taught me to appreciate all sound, and to find beauty in unexpected places. In six weeks the boundaries between noise and music were permanently blurred in my mind, if not completely erased.

When I returned to New York, I found that a number of construction projects had started in my absence. I awoke each morning to a veritable lexicon of machine and work-related sounds: a large crew of jackhammers tearing up my street, men on scaffolds hammering away at the brick facade outside my window, and a symphony of band saws, crowbars, and sledgehammers renovating the apartment upstairs. Trying to work through the constant noise created more moments of desperation than inspiration for me, but the cacophony and hammering always brought me back to the beauty of random rhythms and shifting patterns of utilitarian noise.

Read the other articles:

How I Learned to Love the Wrong Notes

The Score is a series of articles by composers published on TimesSelect

accesible to subscribers of the New York Times